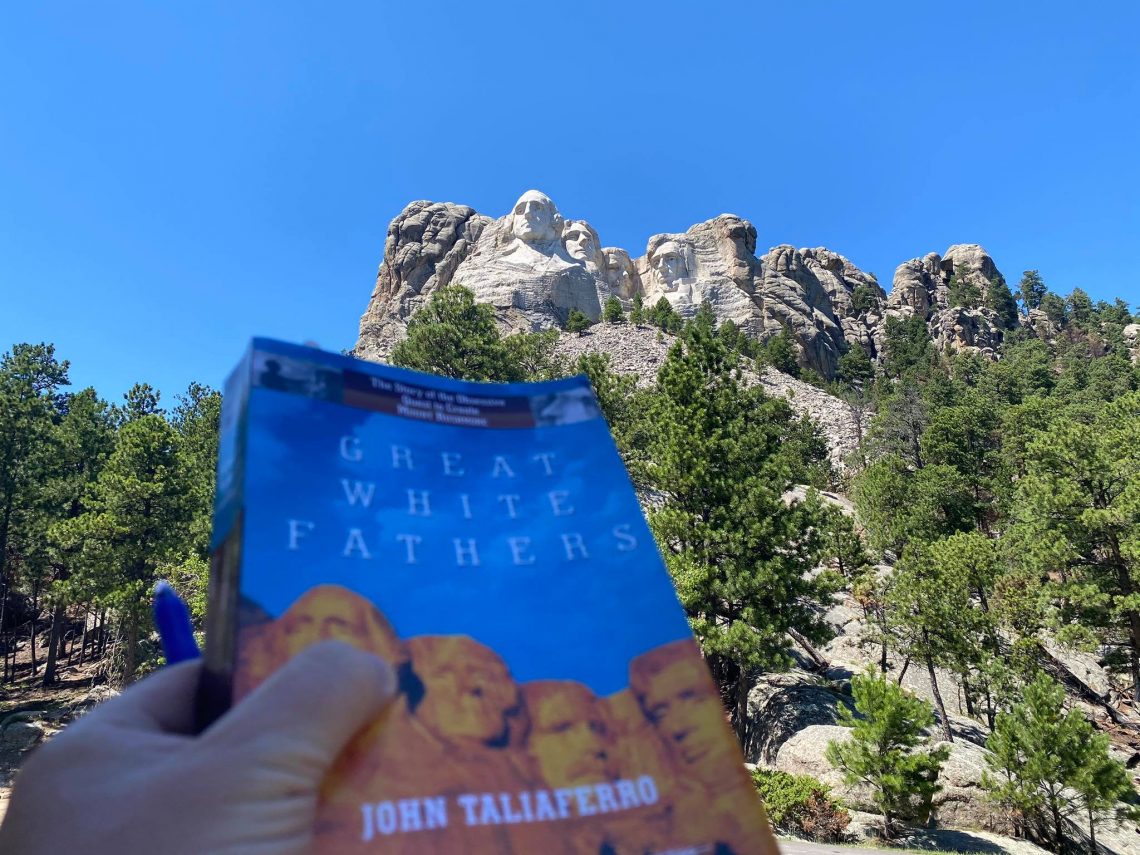

At the Foot of Mt. Rushmore

In the company of crowds, where conversations tend to blend together, I sat down at the foot of Mount Rushmore to finish the last 100 pages of Great White Fathers and heard three distinct comments. One involved a husband telling his wife that the figure to the right of Washington was Benjamin Franklin (that’s Jefferson, buddy). The second was a man complaining that the soap in the restroom smelled bad (certainly serious and contradictory, I suppose). And the third was a woman who snobbishly told her beau that a single guy with a book shouldn’t be sitting at a table with seven seats because it was rude to those with big families (she thought I didn’t hear her, but either way, I got up within five minutes, inviting a family of eight to use the table while I found a single seater in the sun). As I worked through those last 100 pages, I found myself looking up and studying the faces every few minutes, noting the descriptions of smooth scalps and varied scars that I might not have noticed without the text in front of me.

But in the 300 pages or so that preceded that moment, as well as some of the last 100, I couldn’t help but wrestle with the inherent contradictions that Taliaferro must have intended his readers to understand. For this is a monument displaying two warring elements of America’s history, that we are tireless, optimistic, and adventurous idealists and that we are also vile, arrogant, and often cruel stewards of every space we inhabit. For most white Americans, Mount Rushmore is a grand symbol of the nation’s best leaders, those who were self-sacrificing figures, liberating the masses from tyranny and oppression. But underneath the granite is a mountain in the Black Hills that once belonged (and arguably still belongs) to the Lakota Indians whose descendants are now mostly relegated to big city anonymity or the worst kind of small town poverty south of the South Dakota Badlands. For the Lakota, that mountain is a brazen reminder of what they their generations have lost without reasonable reparations. On the surface, it’s easy to rationalize the four presidents carved into the mountain as the best of the best, but Washington killed Indians during the 1760s, Jefferson saw Indians as an uncivilized scourge of the new nation and purchased the land where they would soon be pushed out, Lincoln oversaw the single largest execution in American history (yes, they were Indians), and Roosevelt instituted new policies and ignored old treaties that brought about inevitable demise of the Lakota.

And then there is the sculptor, a man as hard to accept sometimes as the nation he was working for. His associations and comments relating to the KKK are by now common knowledge, but his arrogant and brash personality are lesser known, which could be plenty enough to hate the man. But then you discover he also loved, admired, and believed in the spirit of the Lakota Indians, which further murks up the waters, since he offered to build a memorial for them even more grand than the one at Rushmore, then died before he could start. Add to that the disparity and irony of a man trying to build a memorial that the government would barely fund for 20 years, then afterward spent millions to protect and market.

Sitting at the foot of the Mount, taking in the artistry and the grandeur, I am simply reminded that we are a nation riddled with attributes both honorable and disgusting.

Cutting Corners in Montana