Never the Pot. Never the Water.

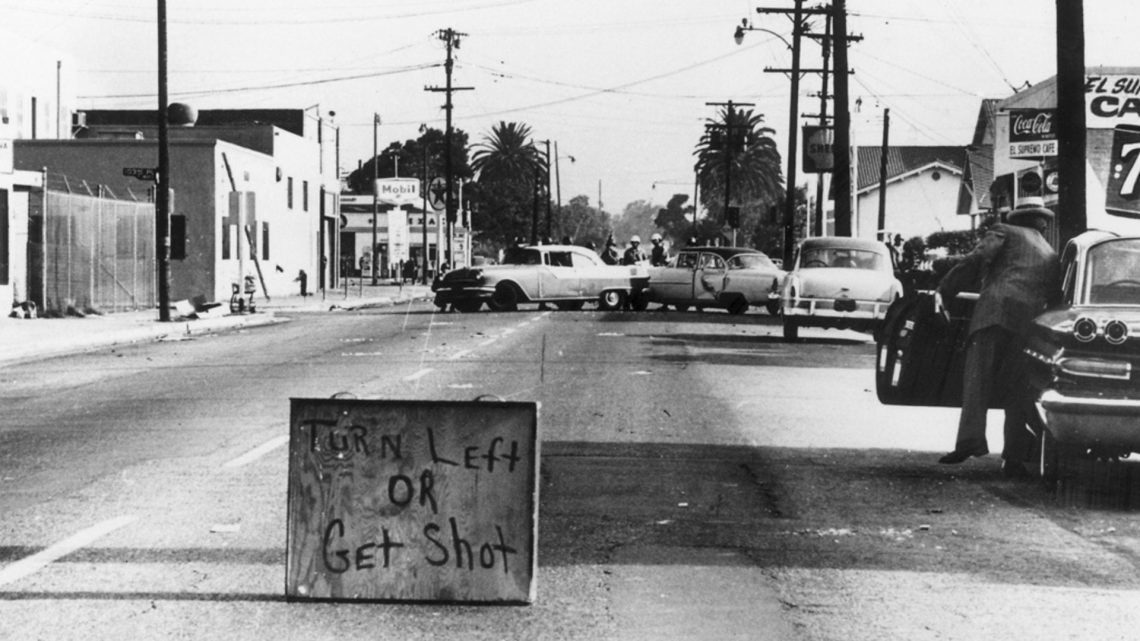

On August 11, 1965, five days after Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law and claimed to have overcome the “last major shackle” of the era, an officer pulled over two black men at the corner of 116th and Avalon in Los Angeles, a neighborhood known as Watts. The driver had been drinking and panicked at the thought of being arrested, which led the brothers to scuffle with the officer as a crowd formed and more officers arrived at the scene. Violence quickly erupted on both sides, with police and crowds each believing the other was hostile. Fires, broken glass, looting, injuries, and fatalities. That was the impetus behind the infamous Watts Riots that lasted six days, prompting similar outcries and defensive stances all across the nation, scenes of violence televised across major cities like Detroit and Newark.

These points in history are documented as “riots” because they involve reactionary violence on a large scale. And looking at these moments from the top down, retroactively, it’s easy to understand how they got out of control, how a few neighbors could have gotten angry at the sight of an officer fighting with someone they knew, how the officer was forced to stand his ground with an inebriated driver despite a growing crowd, how additional members on both ends of the crowd and the police department would have unknowingly added to the confusion and the growing chaos.

Whether that riot or any riot was justified or not has always been a secondary and somewhat irrelevant question for the public to debate. Legally speaking, those who cause damage to property, who cause harm to others, who steal and loot the businesses they’ve broken into, these men and women can be held accountable on a case by case, individual by individual basis, even if it takes a good deal of time to unravel. What the public has to ask is something far more fundamental and vulnerable than pointing fingers at the television, screaming about what “those people” are doing to America.

If you put a pot of water on high and walk away, inherently, the problem isn’t the pot or the water, the problem is you. If you see someone putting that pot of water on high and keep them from returning to the pot, then again, the problem is you. If you participate in this cycle, again and again and again, the problem is always you. Never the pot. Never the water. Something that can be cooled and cleaned after the fact is far less important than admitting there was a reason it boiled over in the first place.

Since America’s founding, our nation has been stacked with communities that villify and destroy other communities, managed under a system that does favors for one at the expense of the other. Fill in the blank with black vs white, Christian vs Muslim, rich vs poor, men vs women, each one being pushed, at one time or another, to a boiling point. In other words, whether we’re the agitators, setting the pot to high and fueling flames of division, or we’re simply the bystanders to the agitators, content to watch it all happen without ever saying anything as the lid bumps up and down, there’s definitely a problem in the kitchen.

Does anyone have a “right” to riot? I suppose not. But I’m fairly sure we all could do a better job of turning down the heat on the oven. And to be clear, there’s a massive canyon of misinformation between violent riots, which can be understandable yet dangerous, and peaceful protests, which are merely the voices of people seeking change in small or large numbers. So while we’re cooling that oven, let’s also not get confused between the boiling water and the recipe books we have sitting nearby, the ones we fill with notes to make everything taste a bit better.