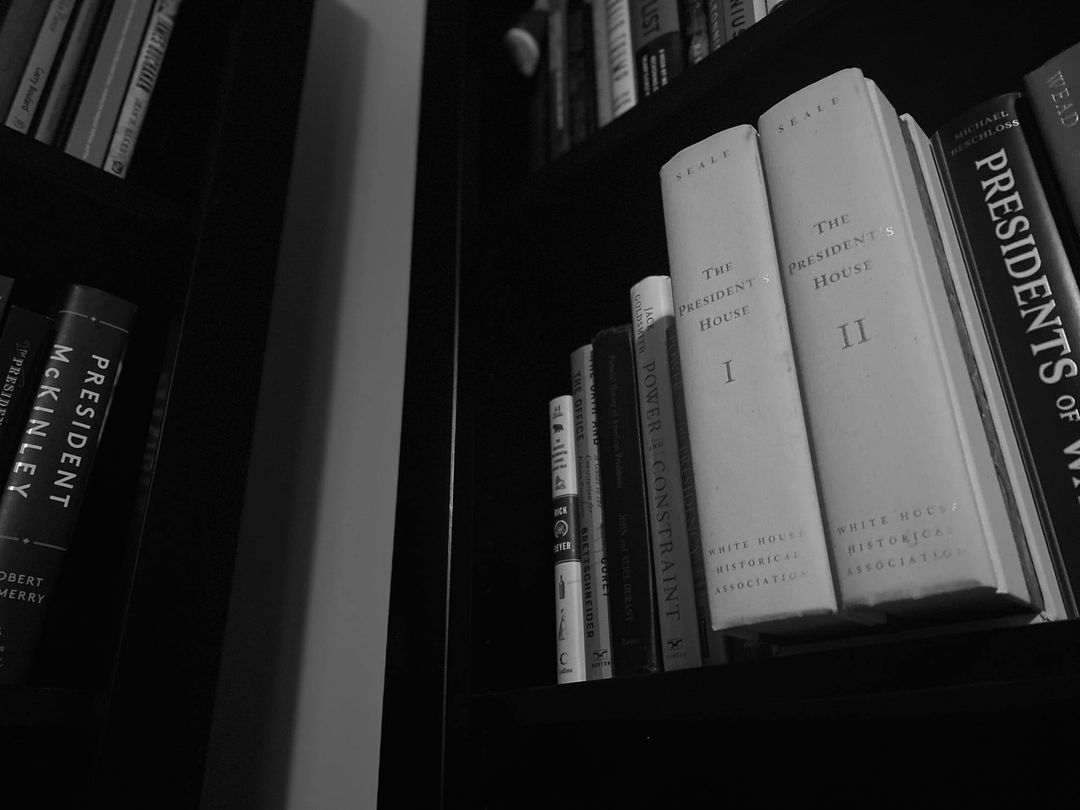

The President’s House

For the record, if you read 1,350 densely-worded pages for hours and hours and hours, marking up every page with lines and notes across two volumes, in less than three weeks, your eyes might actually struggle. It’s like watching television from a foot away for just as many days straight. Turns out, my eyes have been a little batty and blurry of late, but it was worth the potential damage. So here’s my take on William Seale’s history of the White House:

“Breathtaking in its scope. Heartbreaking at its core. On the one hand, covering 200 years of presidential and architectural history is like being a fly on the wall, bouncing from room to room, president to president, family to family, staff member to cabinet member. But Seale goes a step further, making his readers feel like a part of the wall itself, never mind the flies, or the unstoppable rats below. The White House walls, after all, are a better conduit of information than the unsteady flies. From the outside, they see every garden and every building constructed, burned, or torn down over time. From the inside, they hear every voice in every room and they feel the weight of every changing fixture and fickle hand.

Taking on William Seale’s masterfully researched account of the White House and its residents means taking a massive, honest, nonpartisan tour of a nation that somehow manages to survive, year after year, by change and transition at every level, most notably through its executive branch. The tone of Seale’s work loses its patient and enduring heart by Richard Nixon and the 1970s, a heavier-than-usual pacing that seems to avoid the warmth of the latter few presidential families, suggesting a tragic urgency to finish the second volume, but the first 170 years of Seale’s White House history are, at times, both gripping and disarming. Without Seale, for example, the lasting presidential narrative for Andrew Johnson would imply a cold, calculating, selfish man, yet the alternative, which doesn’t deny Johnson’s politically dangerous and racially toxic decisions in the aftermath of the Civil War, shows him as one might imagine a loving father and grandfather at home, a human being who somehow transcends the caricature. Without Seale, for example, we might not know or even consider the White House as a less than glorious residence throughout most of its history, that so many of our former presidents have been unhappy or unsettled in its often cracked and seemingly haunted foundations.”

But alas, this work is, without question, the best account on record of all that has transpired before, during, and since the original construction of the White House, from George Washington through George W. Bush.”